They say you can’t fight city hall. But people can — and it seems increasing numbers do — sue their local government.

They say you can’t fight city hall. But people can — and it seems increasing numbers do — sue their local government.

Since 2010, Hawaii County residents have sought redress for everything from an avocado falling from a tree in a county-owned right of way striking a windshield to contracting a flesh-eating bacteria in a county hot pond to vehicle damage from hitting a feral goat on Mamalahoa Highway to fingerprint dust spilled in a burglary victim’s home causing carpet damage to purchasing a grave site that was already occupied.

Numerous claims involve county workers running into other cars on highways or into shrubbery and fences on private property.

More serious cases have centered on major traffic crashes and high-profile civil rights and Americans with Disabilities Act issues.

Some claimants and litigants get satisfaction. Others don’t.

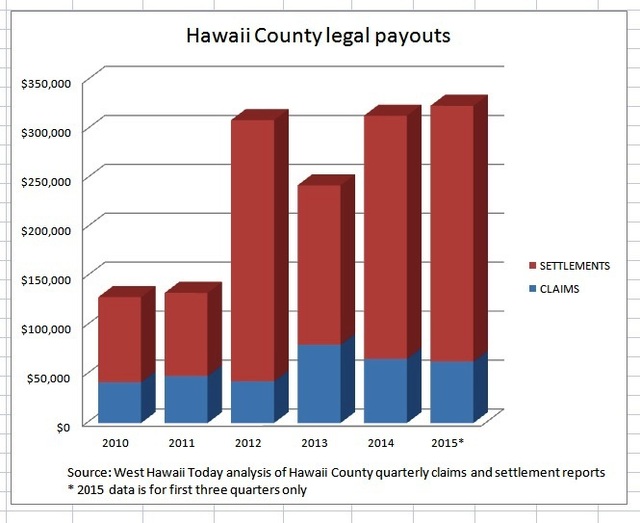

A West Hawaii Today analysis of quarterly claims reports, self-insurance payouts and lawsuit settlements shows Hawaii County has paid out about $1.5 million in settlements and small claims since 2010. After hovering below $150,000 annually in 2010 and 2011, the annual payouts have increased to $324,206 for the first three quarters of 2015 alone.

But Corporation Counsel Molly Stebbins, the county’s chief civil lawyer, says she doesn’t think there’s been an increase in legal payments on claims and settlements. It’s more that the numbers fluctuate year-to-year, and five and three-quarters years simply isn’t a long enough period to draw meaningful comparisons, she said.

Hurricanes, flooding and other natural events can increase the number of claims against county government. And, a settlement in a lawsuit might occur years after the original lawsuit was filed, thus making it hard to draw annual comparisons.

“I don’t think you can extrapolate an upward trend from five years of data. What we pay out in settlements all depends on what cases and claims are filed, so fluctuations are expected,” Stebbins said Thursday. “Overall, I think the total amount of settlements during this period is very reasonable given the potential liability the county was faced with.”

The ability to go to the government for redress is an important right and a protection against an overreaching government, according to the American Civil Liberties Union and other civil rights groups.

“In our democracy, the government is always accountable to the people,” ACLU Legal Director Daniel Gluck said Thursday. “When the government abuses its authority — particularly where the government violates the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution — the people have the right to vindicate those rights in court.”

Last month, the county settled two federal lawsuits brought by the ACLU, and the month before, a third brought by a disabled rider on the Hele-On public bus system. All three cases required changes to county laws as part of the settlement agreement.

“The ACLU of Hawaii recently brought — and settled — two lawsuits against the County of Hawaii. In both cases, the ACLU reached out to the county in advance to try to change the county’s policies without a lawsuit,” Gluck said. “When the county refused, we went to court. In both cases, the court agreed with the ACLU and ordered the county to stop violating our clients’ constitutional rights.”

In one, the county agreed to pay $115,000 and cease the requirement of urinalyses and other medical screenings as a condition of employment for most positions. The county, however, will continue screening employees defined as “safety-sensitive,” such as police officers, and positions regulated by the federal Department of Transportation, about 3 percent of county employees.

The change in policy followed a settlement between the county and Rebekah Taylor-Failor, a Kailua-Kona woman whom the county had previously tendered a conditional job offer. Taylor-Failor had moved from Oregon to Kona to accept a job as a legal clerk within the county Prosecutor’s Office.

The lawsuit challenged the county’s requirement that all prospective employees submit to urinalysis and answer questions about medical history, regardless of the physical duties the applicant would perform on the job.

The other ACLU lawsuit resulted in an $80,000 payout to a homeless man and a rewrite of county panhandling laws to settle a civil rights lawsuit filed by a Kailua-Kona man. Justin Guy was cited in June 2014 while holding a sign off Kaiwi Street in Kailua-Kona saying, “Homeless Need Help.” The citation was later dropped.

A federal judge ruled the 1999 county ordinance was content-based.

“When a politician or police officer can wave a sign on the road asking for the public’s support, but a poor person faces criminal charges for the exact same conduct, that is wrong,” Gluck said at the time.

In the third case, the county agreed to a two-year, $800,000-plus plan to improve services for those disabled individuals who can’t ride the Hele-On public bus system. In addition, the county paid Maui resident Ed Muegge $40,000 as part of the settlement in the ADA case.

Muegge filed the lawsuit claiming he was denied equal access to the transit system because he uses an electric scooter. He said he needs public transportation to get from Kona International Airport to Uncle Billy’s Kona Bay Hotel on Alii Drive when he comes to visit friends in Kailua-Kona.

The largest settlement over the past five years was $245,000 paid to a bicyclist struck by a county Public Works employee with a suspended driver’s license driving a county vehicle in Kailua-Kona in 2010. James Gustin and his wife, Janice, filed the civil lawsuit against Chris Domino and the county. Domino’s license had been suspended because of a past DUI.

Gustin spent five days in the hospital after suffering a head injury, a punctured lung, a fractured arm and multiple spinal fractures, according to the lawsuit.

The other triple-digit lawsuit during the five-year period was a $175,000 award to Blake Parker, who sued in 2012 for injuries he said he suffered when a large metal pipe fell onto his vehicle while traveling on Old Mamalahoa Highway.

Not all the claims and settlements are large. And many claims aren’t paid at all.

The county self-insures its vehicles, so claims are paid directly from county coffers rather than through an insurance company.

Corporation Counsel has the authority to settle claims up to $10,000 without County Council permission. That figure increased from $1,500 within the past few years.

The driver seeking $700 for vehicle damage on hitting the goat did not receive compensation. A rock falling off a county vehicle and cracking a windshield netted $52.08 for the claimant. The avocado cracking a windshield resulted in a $436.30 payment to the vehicle owner.

The family filing a claim after their 3-year-old whose finger got stuck in the door of an elevator at the county building in Hilo withdrew the claim after ascertaining the girl wasn’t injured.

But a claim that the concrete “Toro Statue” at Kailua Park, also known as Old Kona Airport Park, in Kailua-Kona fell and crushed a child’s ring finger netted $40,000.

The homeowner seeking damages for the fingerprint dust was paid $160.

The family seeking to bury its family member asked only for a $100 refund for the burial plot.

The man diagnosed with flesh-eating bacteria after swimming in 2013 in the hot pond at Ahalanui Park with a open wound on his shin received $2,816.

How does the county decide who gets what?

“Our office thoroughly evaluates every case and we only settle when we believe it is in the county’s best interest to do so,” Stebbins said.